“Manson and heroin without end”

Evan Dando, seen from the periphery

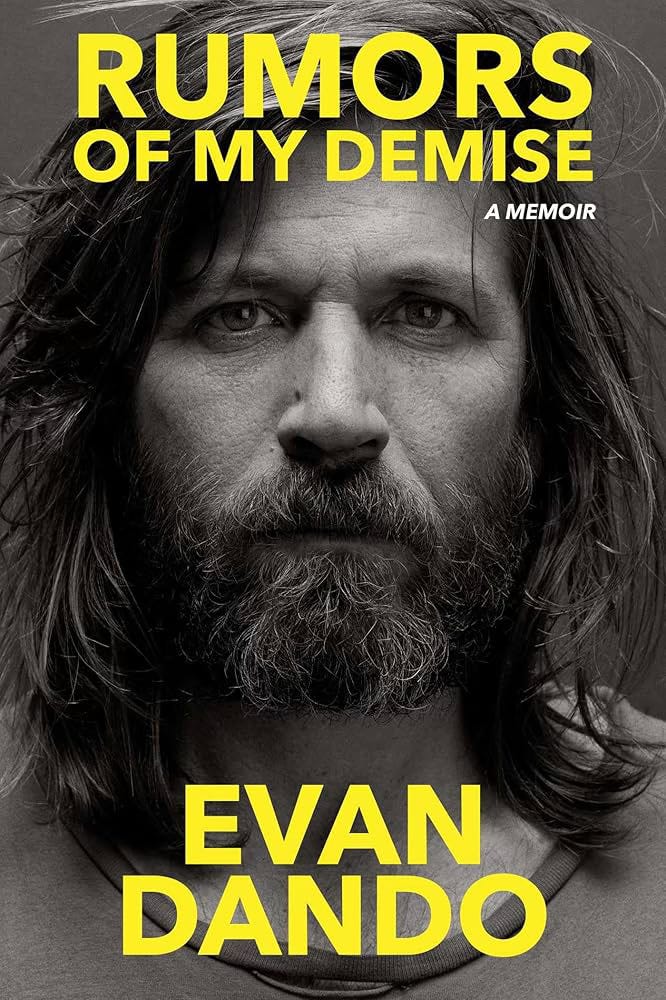

When I learned recently that the Lemonheads’ Evan Dando was publishing a memoir (with unspecified assistance from writer Jim Ruland), I was intrigued. It was a deeper sort of intrigue than the kind I customarily feel about memoirs involving the Boston rock scene of my youth. That was because, to paraphrase the lyrics of a Lemonheads song, I played a bit part in Evan’s life, and he played a little more than a cameo in mine.

The Lemonheads—previously the Whelps, prior to that approximately 527 different names, all of them ridiculous—were founded in the mid-1980s by three teenagers at the prestigious Commonwealth School in Boston’s Back Bay: Dando, Ben Deily and Jesse Peretz. At the time, I was friends with Ben’s musically precocious younger brother Jonathan, known to just about everyone as Jonno. In the fall of ’84, I joined a band that Jonno had formed with a few of his school friends, the legendary (in certain very small circles) Minimum Wage. We rehearsed in the basement of Ben and Jonno’s North Cambridge house, a space that we shared with the embryonic Lemonheads. Jonno and I were 12. Ben was 15, soon to turn 16, and old man Evan was 17. (As he explains in the memoir, he’d had to take freshman year twice at Commonwealth; the first time around, he suffered from a severe disinclination to do his homework.)

I wouldn’t say that I idolized Ben and Evan back then, or that I viewed them as any kind of role models. But over the next couple of years, as they started doing indie-band things—like playing real gigs, printing up flyers and T-shirts, co-opting the Deily/Webb family van and festooning it with LEMONHEADS in fluorescent yellow spray paint, and eventually putting out a seven-inch EP, Laughing All the Way to the Cleaners—I did find myself regarding them with a touch of awe. I recall one weekend afternoon hanging out at the house on Gray Street either just before or just after a Lemonheads rehearsal and bashfully asking Evan whether he knew how to play the Sex Pistols’ “God Save the Queen.” He did, and obliged me with a mildly embarrassed “Okay, here’s one for the kid” grin. I enjoyed the brief attention.

The collage of photos and flyers that decorates Rumors of My Demise’s endpapers rings plenty of recognition bells for me; almost every one of the flyers is advertising a show at T.T. the Bear’s Place in Cambridge, where I saw several Lemonheads performances. In the book’s central photo section, there’s a shot of Ben, Evan and Jesse playing at Brandeis University in late ’86. This gig was a real coup for the young band, as they’d wrangled a slot opening for the Ramones. (Ben, a Brandeis freshman then, knew somebody who knew somebody.) You don’t see 14-year-old me standing in the crowd stage left, but you’ll have to take it on faith that I was there, and I had the T-shirt too. Evan writes about the coolness of seeing the full-black-leather Ramones in the flesh, and I’ll second that, but one thing he doesn’t mention is that some smart aleck—maybe a Lemonhead crony?—got out of control with the dry-ice machine during the headliners’ set. As soon as Joey, Johnny, Dee Dee and Marky took the stage, they were surrounded by a thick curtain of smoke and could barely be seen for most of the show. No problem hearing them, though.

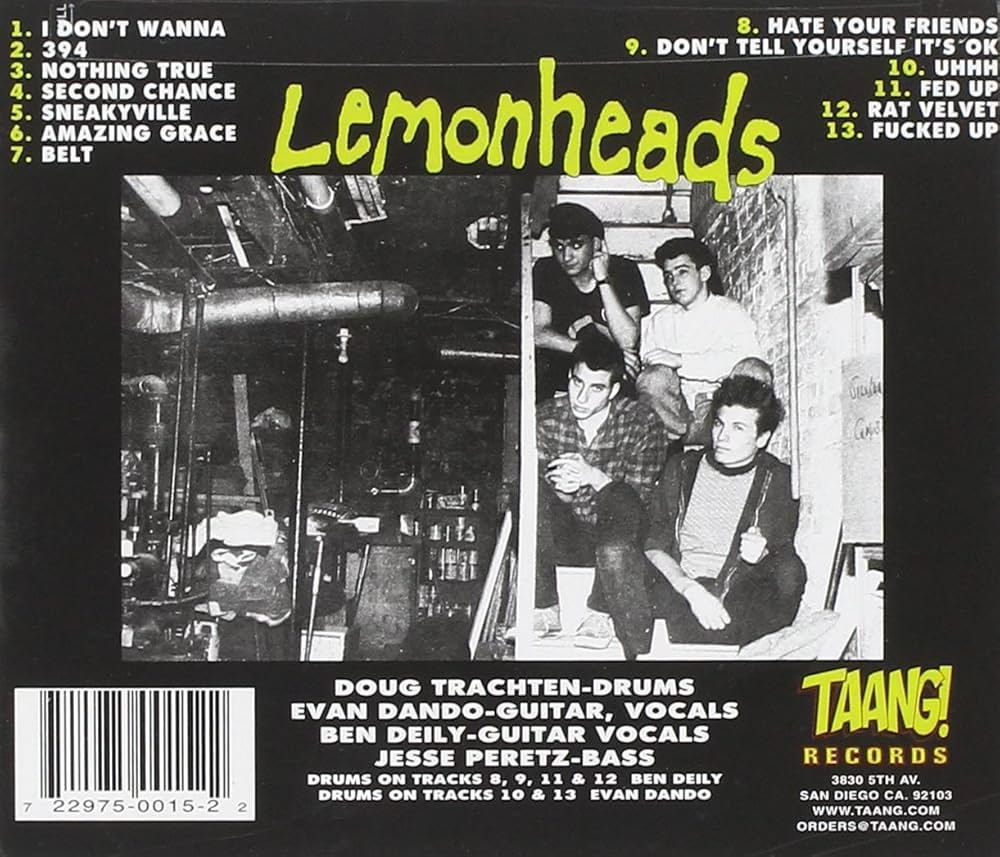

In all honesty, the early Lemonheads were kind of a joke. Evan admits as much, calling them “a ramshackle punk rock party band that no one, including ourselves, took very seriously.” But when they signed with the Boston indie label Taang! and put out their first full-length album Hate Your Friends, complete with back cover photo taken down in the basement where we all rehearsed (see below), I began detecting signs of seriousness. Ben’s “Second Chance” wasn’t just a bona fide pop song, it was a bona fide good pop song. (Then they blew my mind by making a video for it. A video that MTV actually aired!) As for the album’s prime Evan tune, “Don’t Tell Yourself,” I was stunned by its beauty—sensitive and sad but still rocking, with a heart-piercing wordless melody in the bridge. Its author says that it remains one of his own favorite compositions, an opinion apparently shared by another Bostonian of note, the Lyres’ Jeff Conolly, as well as yours truly.

As much as I was starting to like the Lemonheads’ music, other aspects of the group struck me as less thrilling. Principal among these were the basic mechanics of being in a “professional” rock band. One late night after a gig at T.T.’s—or maybe it was a late afternoon, following an all-ages matinee where they shared the bill with local faves the Volcano Suns—I stood and watched as the guys lugged their guitars, amps and drums back out onto the street and into the big blue Dodge van. This part of the job did not look like fun. “Now they’ve gotta drive all this stuff back home,” I thought, “and unload it all once they get there. And for the next gig, there’ll be more loading and unloading. And loading. And unloading. Over and over.” At an early age, I’d realized something important: that the life of a working musician might not be for me.

Another not-so-appealing feature of the band was a passion of Evan’s that seemed silly then and seems even sillier now: He was simply enthralled by anything relating to Charles Manson. (He even covered a Manson tune on the Lemonheads’ second album, Creator.) A substantial chunk of Rumors of My Demise attempts, unsuccessfully, to defend his growing obsession with a creepy cult leader who orchestrated serial murders. At one point he writes, “It’s trippy to think that in the span of a few months, Manson went from being a trendy, hip musician who’d written a song on a Beach Boys record to a murderer.” News flash: No one who wrote a song on a Beach Boys record in 1969 was trendy and hip. A page later, he adds, “Ultimately, Manson exposed the hypocrisy of the news media.” Really? Is that what he did?

Similar instances of weird semi-justification for stupid and often life-threatening behavior (both Evan’s and others’) crop up increasingly as the book continues and the author descends deeper into the addiction to alcohol and multiple drugs for which he has, unfortunately, become most famous. For example: It was news to me that Dando began sleepwalking and experiencing night terrors from an early age. These episodes became more elaborate and scary as he got older; he’d leave the house and go out walking while still asleep, climb onto balconies and fire escapes, putting himself in real danger without being aware of it. Somewhere along the line, he deduced that whenever he took heroin, his somnambulism and vivid nightmares would cease. And there you have it, a perfect post-facto rationale for junkiedom. “If there was something that stopped you from waking up in the middle of the night and screaming your head off, would you take it?” he writes. Maybe, but I have the nagging feeling that he hadn’t been looking all that hard beforehand for a real solution to his problem. Surely he could have found something less tricky to obtain? More regulated? Less addictive? Cheaper?

Taking such a path might have meant less partying with supermodels, though. And in Evan’s case, the trickiness-to-obtain part is irrelevant. This child of privilege didn’t have to experience the hassle of buying smack himself; he had people for that. “I never wanted to go score the drugs,” he acknowledges. “I would pay extra just to stay home.” Only a couple of pages earlier, he writes, “It always surprised me how many people were willing to hand the reins over to agents, lawyers, and handlers … For better or worse, I didn’t do that.” Except for the purchase of injectable substances, apparently.

Now and again, an episode occurs that almost makes one feel sympathetic toward our protagonist in his steep decline. Another thing I didn’t know about Evan was that he was living in the shadow of the Twin Towers on September 11, 2001. The tale he tells of escaping from his apartment building that day is legitimately harrowing. So what did he do in the wake of such horror? Volunteer site cleanup, perhaps? Survivor support? Checking in with neighbors? Nope, he got blitzed on a combo of nitrous oxide and Vicodin, and stayed that way for weeks. How could anyone have thought otherwise?

As you may have suspected by now, I find Rumors of My Demise a frustrating book, written by a frustrating person. At times, Evan shows an awareness of his own bullshit that’s as charming as it is perceptive (“It’s kind of funny that my big takeaway from rehab wasn’t to stop doing drugs, but to stop talking to the media about doing drugs”). At others, he castigates unnamed people at his record company while remaining willfully oblivious to the natural consequences of his self-sabotage (“[Atlantic] just wanted me to get the record done before I overdosed”—um, yeah, they did, because they’d invested a lot of money in an obvious loose cannon and were trying to make at least some of it back). He can ramble in an endearing way and crack self-deprecating jokes that suggest significant intelligence, then without warning he’ll drop a bizarre aside that couldn’t read more like an archetypal clueless rock-star caricature: “New Zealand is the first place where things were going so well I thought about trashing a hotel room.” Yeah, just like everyone.

So where did all this mess spring from anyway? It’s hard not to be at least a little alarmed when Dando writes that his lawyer dad, who separated from his model mom nine years after Evan was born, snorted coke, liked to get his son drunk and essentially left him and his older sister to fend for themselves in a house on Martha’s Vineyard during the summer of 1981, when Evan was 14. Pinning everything on daddy issues oversimplifies matters, of course. As Dando himself states, “Destruction has been a recurring theme in my life … It would be easy to blame it on my parents’ divorce, but I was a terror before they split up.” Whatever the explanation may be, it’s fairly clear from reading his memoir that something essential is missing inside Evan Dando and probably always has been, some solid, stable core that might have grounded him and kept him from squandering his obvious talent, straying down the path of oblivion and becoming the worst kind of showbiz cliché. For someone who kinda sorta knew him when and was thrilled by his early-’90s rise, the whole sordid saga that followed is disappointing and sad.

I’d love to report that Rumors of My Demise has a satisfying conclusion, but I can’t. Now married to his second wife, Evan has moved to South America to get away from the drug scene on Martha’s Vineyard, where he’d previously moved to get away from the drug scene in New York. I have no sense whatsoever that he’s turned any major corner in his life or will do so anytime soon. He appears to understand that the ragged course of his career doesn’t exactly constitute the strongest endorsement for being high all the time, but he’s chosen to resign himself to that reality. “I don’t want to be that annoying person who always causes trouble,” he writes toward the end, “but who am I kidding? Deep down that’s who I am.” Maybe he’s really reached the point of being honest with himself. I have my doubts about that.

Ben Deily left the Lemonheads in 1989, just before the band signed with Atlantic. (A few years later, he wrote a song, “Name in Vain,” that not so subtly accuses Evan of selling out for major-label bucks. Sample couplet: “That’s how it goes when you hate your friends/Manson and heroin without end.”) In the decades following that split, my path has crossed Evan’s only twice. The first time was in 1992, when Jonno and I went to see him and a short-lived Lemonheads lineup of Juliana Hatfield (bass, vocals) and David Ryan (drums) give a live preview of the songs that would soon make up the It’s a Shame About Ray album at—of course—T.T. the Bear’s. The new material sounded great, the future looked swell, and we had a brief but friendly chat with Evan after the show.

The second time Evan and I reunited was in 1996, when I interviewed him in New York for Musician. My story appeared in the magazine’s January ’97 issue. He seemed to be in good health; the true wilderness years hadn’t started yet. When we met at a restaurant in Chelsea, Evan recognized me immediately, and we both got a kick out of meeting again in this way: the once-wannabe rock star now the real thing, the former kid on the periphery now … well, still on the periphery but making a living out of it. Because the article focused almost completely on songwriting, I neglected to mention my youthful connection to Evan, not thinking it was relevant. If I were to write it again today, I’d have said something about that, if only in the interest of full disclosure.

In that interview, Evan said, “All the songs are different. They all come from some sort of inner hum that produces chords. Then the chords dictate a melody and subject matter. You’ve just got to work out a melody that’s a little different. I basically follow the hum inside, and try to mean it. I haven’t quite figured it all out yet … I’m still working toward something.”

Today, when I listen to “Don’t Tell Yourself” or “Out” or “Stove” or “The Turnpike Down” or a long list of other Lemonheads songs from the ’80s and ’90s, that’s the Evan Dando I hear. The one working toward something, following the hum inside. That Evan Dando is still worth hearing. He may show up on Love Chant, the Lemonheads’ first album of originals in nearly 20 years; I haven’t heard it yet but I hope so. I just wish we all could have heard more from that Evan over the past three decades, instead of the one who wasted his time shooting up with Courtney Love and turning Johnny Depp’s house into a pigsty.

This piece was a far better read than “Rumors of My Demise” could possibly be. Thank you.

ooof. I saw a blurb about the book and thought, "I'd kind of like to read that, but I'm afraid of what I might learn."