Over the past couple of weeks, I wrote a lot of words about a subject that many, many other people have written a lot of words about over the past couple of weeks. Surely you know the one; it starts with e, ends with n, and rhymes with lethal injection. The writing was good, I thought, and the points were trenchant. It was probably beneficial to my personal well-being to do it. None of it has been published on this page. None of it will be. I don’t believe I have a single idea on the topic that’s original. Others have already said it all. Adding one more opinion to a cybersphere already overstuffed with them isn’t going to help anyone’s life, including mine.

And so I turn with relief to a subject that I’m pretty sure a lot fewer people have been writing about: the Lydian mode.

For those who remain uninitiated, the Lydian mode is a pattern of seven musical notes. It’s identical to the Ionian mode, a.k.a. your garden-variety major scale, in all but one crucial respect. A standard major scale has a standard fourth degree (fa if you’re prone to solfège)—F in the key of C, for example. The Lydian mode raises that fourth by a half-step—F-sharp in the key of C. Adding the half-step produces a harmonic effect similar to what you get if you take a major chord and then superimpose another major chord a whole step above it; sticking with our chosen key, it’s like playing C major and D major simultaneously.

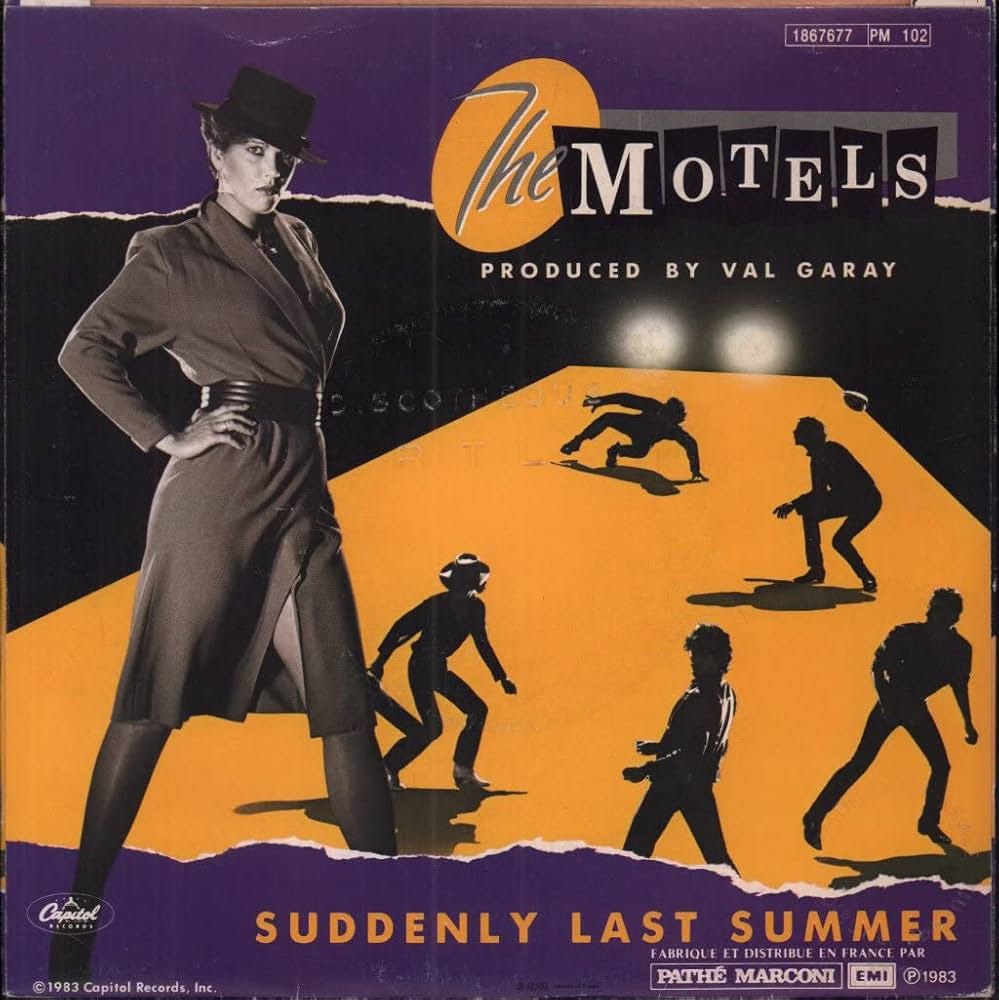

A Facebook friend of mine recently posted that, in popular music, the Lydian mode is “the mode of the ’80s.” That prompted another Facebook friend of mine to comment on the mode’s special prominence in the work of one particular band from that era, Los Angeles rockers the Motels.

This is the kind of stuff certain types of musicians consider small talk. It also led me to spend an afternoon with the music of the Motels. Not for nostalgic reasons, mind you, at least not mostly (though I must confess all the goings-on related to … heck, I’m just going to keep calling it this … the lethal injection have me mainlining Albert Camus and the Cure like it’s 1987 all over again). No, the listening session was principally for purposes of confirmation.

Consider it confirmed: The Motels were very ’80s, and very Lydian.

You can hear that in the two Motels tunes most people know, the hits, “Only the Lonely” (1982, not the Roy Orbison song) and “Suddenly Last Summer” (1983, not the Tennessee Williams play/film). For “Only the Lonely,” the Lydian mode makes its presence felt big-time in the chorus’ key line, “Only the lonely can play.” The melody of this line starts over a D-flat chord, and of its first five notes, two are Gs, the sharp—i.e., Lydian—fourth of D-flat: “Only the lonely …” For “Suddenly Last Summer,” turn to the start of the pre-chorus: “One summer never ends.” Those two italicized syllables, arguably the song’s dramatic pinnacle, are G-sharps over a D chord. Raised fourth; Lydian again.

These aren’t the only (the lonely) places in the Motels oeuvre that get Lydian. The central riff of “Suddenly Last Summer” is in A and sports a D-sharp. “Take the L,” also from 1982, pivots around an F-sharp over C in the melody of the chorus: “Take the L out of ‘lover’ and it’s o-ver …” And I could name several more examples.

All very evocative, for sure. But evocative of what?

Both suspended standard fourths and suspended Lydian fourths convey a feeling of floating above chords. They’re alluringly indecisive. They leave you hanging (as implied by the term “suspended”). But due to their relative positions on the scale, their emotional functions are different. Because a standard fourth is closer to the third, its core wish is to descend, to ground itself, to find resolution on earth. Because a Lydian fourth is closer to the fifth, it aspires to the stars. It yearns to rise, up to where it’s already so close to being. On its own, though, it’ll never get there.

This emotional function is exploited with great skill in the melodies of “Only the Lonely” and “Suddenly Last Summer.” In both cases, the fourth does reach the fifth, but just for an instant, before plunging backward, away from the heavenly goal. The melody supporting the words “Only the lonely” in the second line of that song’s chorus struggles between A-flat (5) and G (Lydian 4), then descends to E-flat (2), another unresolved note on a lower rung of the ladder. The first line of the “Suddenly Last Summer” pre-chorus starts on G-sharp (Lydian 4), falls to F-sharp (3), then pushes itself to leap again, in clever chromatic style, from F (sharp 2) to F-sharp (3) all the way to A (5). But the way Motels frontwoman Martha Davis sings that line, the melody starts to drop back down from the A almost as soon as it’s attained. The effort was exhausting; the next line doesn’t dare go any higher than F-sharp.

In other words, the Motels’ use of the Lydian mode in these two songs evokes old dreams that once came true but only briefly, dreams that required too much work and are too far away now to be refulfilled. Melody, harmony and lyrics work hand in fingerless glove to conjure a mood of wistful melancholy.

I’d love to tell you that the rest of the Motels’ catalog warrants similar musical analysis, but it doesn’t. Their early, pre-“Only the Lonely” work is a collection of spare parts that have potential but don’t fit together well; their later work is very ’80s in a non-Lydian, and non-good, way. Still, those two singles, the hits that deserved to be hits, maintain their deep appeal.

A related note: I’m currently working on two albums of original music. At least five of the songs have significant Lydian moments. Am I being intentionally retro? No. But then again, I am a child of the ’80s.