Previously on The Countoff, I announced the April 2 release of my new album Exposed Erratics, explained the meaning of its title and offered some notes on its first six songs. Now here’s a little background on the other six.

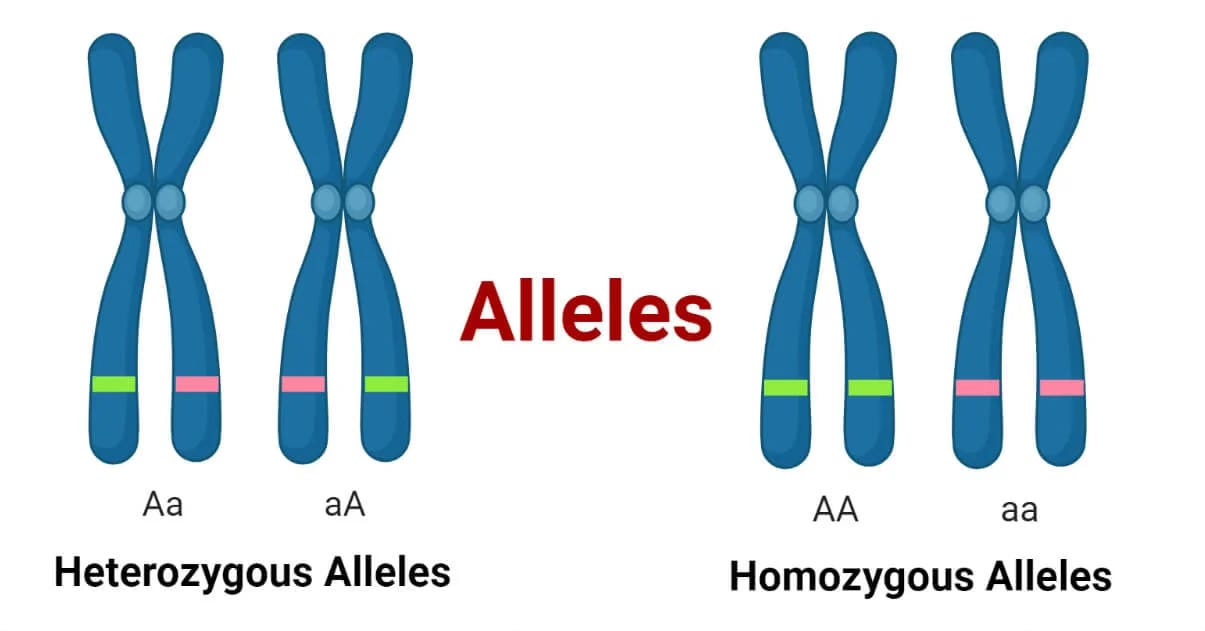

Way back in the early ’90s, shortly after my family returned to Cambridge full-time following a three-year sojourn in New Bedford, Mass., I recorded the first, instrumental demo of this song. The date on the cassette is April 29, 1991. The backbone of the music—the main riff in D and the spacy interlude in E—came out of jams with Skysaw, a band I’ve mentioned before. On December 28, 1991, I recorded a second version, this time with a vocal and lyrics. (One of my better demos, which you can hear in my Soundcloud demo compilation Box of Urchins Not Received.) Both versions bear the title “Multiple Alleles.” This is a term from genetics that I think I picked up in I. Bernard Cohen’s history of science class at Harvard. According to the National Cancer Institute, an allele is “one of two or more versions of a genetic sequence at a particular region on a chromosome. An individual inherits two alleles for each gene, one from each parent.” Thus the couplet “Signify and multiply/Simple biology.” At some point I had the astonishing revelation that “Multiple Alleles” was not a good title and changed it to “Operate Alone,” words that were actually, y’know, repeated in the song. Though the lyrics are kinda vague, as they often were for me in those years, the principal subject here is free will. We may desire to “operate alone,” but how much can we really do so? How much of our lives is predetermined by our genes? The 19-year-old author, not surprisingly, arrived at no answers, but given his relationship with his parents at the time, it’s also not a surprise that he was pondering such questions. How this all relates to an “experience in bronze that once was mine” I’m not even going to try to explain, but I still like that line—it’s the process of creation in a nutshell.

The newest song of the bunch and the most obviously American-sounding, like a Paul Westerberg/Bob Mould co-write. Chords and melody were written on Valentine’s Day 2023, recorded quickly on my phone and given the title “Orange Brothers Lullaby” in reference to the recent arrival of two cats, William and Frederick of Orange, in our home. (In a ’90s flashback, the tuning is the same as that of “Armored Ignition”—thanks again to Tim Mungenast.) The words came a year later, inspired by two things. First, staying at the Hampton Inn on Alden Road in Fairhaven, Mass., when I visited my mother for what turned out to be her last birthday, June 7, 2023. This was the same time that smoke from Canadian wildfires was changing the color of the sky and I was, still unknowingly, coming down with a second case of COVID. A woman and (I presume) her young son appeared to be living in their car in the hotel’s parking lot. The kid was jumping around, digging in the dirt, climbing on top of the car and its overhead storage bin, hitting trees with sticks. Future militia member, I thought. The mother was in the driver’s seat of the car, rendered almost invisible by the piles of stuff inside: clothes, sheets, papers. For a while I weighed mentioning what was going on to somebody at the front desk, but I had the feeling that might cause further trouble. In the end, I felt so lousy when I checked out that I chose to keep social interaction to a minimum. Probably just as well. But the whole situation bothered me. Still does.

The second thing that inspired the lyrics was reading Costica Bradatan’s In Praise of Failure early in 2024. In the book’s prologue, right on the first page, Bradatan notes that our lives begin in eons of nothingness and end in eons of nothingness. Therefore, “[n]o matter how we choose to reframe or retell the facts, when we consider what precedes us and what follows us, we are not much to talk about. We are next to nothing, in fact.” This statement reminded me of mother and son in the Hampton Inn parking lot. They were visibly living next to nothing, but on an existential level we all are. Because this concept of next-to-nothingness is very Samuel Beckett, I threw in a line about failing better one more time, and “Orange Brothers Lullaby” became “Next to Nothing.” The completed song was demoed March 20, 2024. Two acoustic guitars, two voices, full stop. With only small revisions, that demo became the final recording.

I already had the title when the first, solo guitar instrumental demo of this song was recorded on August 29, 2019. I don’t know what inspired it, but it struck me as a nice phrase. That initial version didn’t have the middle section with the clangy chord and sexy riff; those bits arrived on November 28, 2020, while I was testing out a Yamaha guitar amp with my DADGAD-tuned Telecaster in an empty apartment (long story). Within a few minutes, “Swamp Riff Redux” had been written and recorded on my phone. Evaluating my various bits and pieces in early 2024, I thought that “Words Turn to Whispers” and “Swamp Riff Redux” could work well together. Lo and behold, they did. And so we have one of the few songs I’ve written that, if it’s to be played correctly, requires two guitars in two different tunings. When it came time for writing lyrics, well, the sexy riff made me think of my wife, and soon the meaning of the title “Words Turn to Whispers” became apparent. I cut a second, fully arranged demo on March 22, 2024, and that forms the bedrock of the final recording, with my original bass and drum parts mostly replaced by Michael Gelfand and Peter Catapano.

First demo, with vocal but no lyrics, recorded January 28, 1995 and titled “Under the Floor,” basically a description of my emotional state at the time. The descending chord/melody combo at the beginning was almost a painting in sound of the way things seemed literally to be going down. It also was stolen from Stevie Wonder’s “Don’t You Worry ’Bout a Thing,” a theft so obvious that when I presented the song to the other members of Fuller for consideration four years later, it quickly became clear that I’d have to modify the opening phrase, which I did. I added words and electric guitar to the original demo on May 7, 1995, the day after I finished “Twenty to One.” That was a productive week. Here’s the thing: The words describe a dire situation—I’m lost, I’m sinking, everything good is over, I might as well die—and yet the music is tremendously inspired, so original (the Stevie rip notwithstanding) and surprising. Looking back on it now, I feel like I had something I desperately needed to express but didn’t know how to start, so I took the Stevie bit to get me going. Then, once I’d gotten somewhere, I could go back and change the beginning. Not a bad way to do it, really. Fuller played this song for an audience once (I think), at the Mercury Lounge in 1999, and I played it solo a few times in 2005. I came back to it in the fall of 2022 and cut a slightly rearranged solo acoustic demo on my phone, then did a third demo, with more instrumentation, in March 2024. That third demo, with various additions (like Peter’s drums and percussion) and subtractions (some but not all of my drum machine parts), is the foundation of the final studio recording.

A collaboration with Michael Gelfand, who wrote most of the underlying music; I wrote the vocal melody and all the words. The initial solo acoustic-guitar instrumental demo was cut by Michael on May 30, 2015, with the title “May Daze.” Sometime later, he sent it to me and I flew it into Pro Tools. At first I tried to overdub onto his recording, but then I came up with another part for the song (the semi-chorus, the first line of which is “Every half-known reason falls away”). Thus, on March 12, 2016, I started a new demo from scratch, with a pile of overdubs. Like “The Differential,” this could have been recorded for Germination but didn’t seem cooked enough yet. I rehearsed it once or twice in 2017 with Peter and Michael. In February of 2024, I added yet another vocal to the existing demo, mostly to fill out the big round at the end. For the studio version, we rebuilt the song from the ground up and added even more overdubs than before, including multiple Mellotron parts (never a bad thing).

“The Ballad of the Fisherman’s Cap” on I Call Time tells a mostly true story in which my late father and I both figure. “The Clock Inside” goes further and addresses my father directly. I ask him to explain to me what the “master plan” is—i.e., the master plan for me, what I’m here on earth to do. I refer to his love of Hemingway and suggest that influence may not have been entirely good for him. I want him to stay with me, to stay alive. But I already know that’s not possible (he’d been gone more than 20 years when I wrote the song). And so I take something I’ve learned from him and make it my closing message for the album: Life is short, so don’t waste it being miserable all the time.

The first demo of this instrumental piece was recorded solo acoustic on cassette July 11, 2012, shortly after my wife and I returned from a trip to the Friuli Venezia Giulia region of Italy to promote the Italian translation of my Radiohead book Exit Music. Our hotel in the city of Udine was called Al Vecchio Tram (by the old tram). The trip was amazing—thank you, Mario Rimati, for making it possible—and the warm feelings it generated are reflected in the music, along with a certain Italian-ish classical stateliness. While going through old recordings to develop in early 2024, I was particularly struck by this one. It felt like a perfect closing statement, and it could do with some strings. This would connect to the classical vibe, yes, but adding other instruments could also simplify my part; the guitar would no longer have to cover everything. Working with Claudia Chopek on the arrangement for string quartet (the first I’ve had on a record) was a huge thrill. Many thanks to her and the other members of the quartet: Denise Stillwell, Angela Pickett and Yair Evnine. The last notes of “Al Vecchio,” and Exposed Erratics, are a fond farewell, leaving the listener—I hope—with a sense of quiet strength.

A reminder: You’ll be able to hear a fair portion of Exposed Erratics, along with other songs of mine, performed live by the Mac Randall Five—featuring Pete Galub (guitar), Jeff Hudgins (reeds), Michael Gelfand (bass) and Peter Catapano (drums)—on Saturday, June 28 at Room 52, 212 E. 52nd St. in Manhattan. Doors open at 7 p.m.